The Wild Mind – Part II

Scientology 1.0.0 – chapter 9

In the previous chapter, I made a list of some of the kinds of thinking and experience that are almost certainly required if anything as bizarrely complex and impressive as modern civilisation is to exist. These ideas occur somehow and, enfolding the ideas that preceded, build towards more sophisticated and complex thinking, a ladder of more and more advanced human development. Eventually, as the ladder extends, it gets us to the kind of reality that we exist in today, and if we play our cards right, the ladder may extend ever upward to the stars and beyond.

Pooh-poohing things like magic and religion as ridiculous superstitions of our illiterate forefathers may be de rigueur in the halls of academia and the mass media, dominated as they are today by materialists, but, as I propose, this is akin to kicking out all the rungs of a ladder beneath (oops!).

Of course, there are things not on the list, and there are probably multiple ways to arrange and compile them, not to mention possible problems with sequence and simultaneity. Still, I continue with my comments and descriptions of each thing on it, not because most readers won’t know about them, but because this is my way of laying out a bit of the background, the provenance, you might say, of Scientology 1.0.0 in preparation to discuss its inception and history.

Now, to continue…

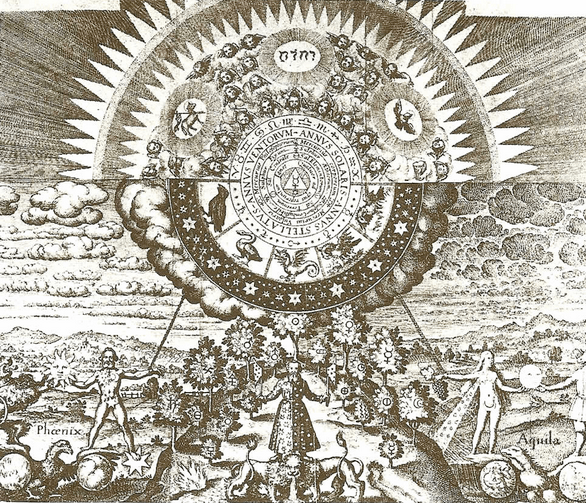

Magic

Magic is definitely one of those rungs, and like all the other rungs, it plays a key role in life all the way through, whether one knows it or not.

Before the beginning of Western civilisation (dated to approximately 4,000–4,500 B.C.), there were towns (the Urban Revolution, 9,000–10,000 B.C.), and before towns, there were tribes, and those tribes consisted of people working with good and useful ideas. They were smart people, and we are a huge success not despite them but because of them.

There is a big difference between the complexity of a tribe, consisting of maybe fifty to a hundred and twenty-five related people, and a civilisation, consisting of thousands, and now millions and billions. Small tribal groups don’t need organised religion or philosophy per se, but they do need magic, because that’s how the world mostly seems to be. Harnessing this invisible power is how to be in control.

Acting as a causative agent in the world, magically or otherwise, rather than the effect (victim), is a key factor in success. This is because persistent fear and apathy, particularly when stemming from feelings of inadequacy in the face of a vast and enigmatic universe, consistently lead to failure. Even just recognising and then working with all the myriad invisible forces to achieve a positive view of life would appear to go a long way towards obtaining basic survival. In addition, understanding the magical nature of the universe is also necessary in order to gain true enlightenment, as I shall explain.

It might be that our ancient ancestors set their groups up similarly to the way hunter-gatherer groups are in the world today. In each group, there was, of course, a hierarchy of some sort. Then, off to the side, there was a specialist who worked magic. This professional would act as a bridge between the group and all other levels of reality and perception, as well as the invisible forces, to help the group survive and move forward.

Today, magic plays, and still plays, this vital role at all levels of groups, from the simplest tribal groups to modern civilisations consisting of hundreds of millions. Maybe we don’t see this fact in this way much here in the West, but anybody who has paid attention to the thousands of different ceremonies and rituals all over the world will see the magic in practically all of them.

In my opinion, though, there are ways it can go dangerously sideways. Throughout history, the actual workings of magic, often conflated with superstition and trickery, have led individuals and groups into significant trouble. Famous examples are human sacrifice, witch trials, and so on.

Then there’s our modern era, where magic just seems to be either silly or weird.

Definition

Thinking about invisible forces (as much as “force” plays a role in the mind or outside of temporal reality) makes me think about the world as it was before towns. I mean, think of this: when you live in a time on the planet where your group is only about a hundred or so people and your contact with other such groups is, probably, seasonal, you live in a world that’s hard to picture today (unless you visit the Serengeti or some similarly unvisited, unpopulated region… and stay there without Wi-Fi for a thousand years). Because there were so few of these groups back then, relatively speaking, the world is one of truly vast spaces (just painting a picture here). A world that is also often quiet or rhythmic (seasides, insects) or filled with white noise (rivers and waterfalls) when it is not punctuated with the snarls and howls of predators. And, at night, dark! Depending on where you are, nights go on forever, and if you live where there is often cloud cover, such as the Nordics did, it gets very dark indeed, something not experienced much these days if you live in a town or city.

Time doesn’t exist at all in the way we know it today, and our attention to everything in the world is at a level that, by comparison, would most likely make many of us in the present seem less asleep than dead. When there’s a disruption, like a thunder storm or an earthquake, it gets noticed! This vastness of space, the deafening quiet, and the eternities of time and night—plus attention to everything (and so much more)—would, I think, have to make certain things seem plain. Such as magic.

Magic: the power of apparently influencing events by using mysterious or supernatural forces. From late Middle English, from Old French magique, from Latin magicus (adjective), late Latin magica (noun), from Greek magikē (tekhnē) ’(art of) a magus’. (Note: a magus is a member of a priestly caste in ancient Persia, the sort that came to say hello to Jesus of Nazareth when He was born.)

I admit, I actually don’t know much about magic, but it’s easy to guess that it’s been a primary driving force, for good or ill, since the dawn of time. Things like shamanism, divination, various healing practices, and so on, are all ways and forms of doing magic. So it’s my supposition that these complex arrangements with invisible dimensions and forces, and the myriad ways of working with them, were a key factor in achieving individual and group survival.

“Invisible dimensions?!” screeches the materialist, “there you go, down the rabbit hole and into the weeds!”. Yes, here we go indeed! I’m aware, of course, that it can be argued that success was achieved despite, or regardless, of these practices but how would one know? Personally, I don’t think so.

I suppose, too, some people might think that what was thought of as magic was simply poor observation (the eternal struggle to define causes), but I’d argue, again, how would you know? You can really only make that claim in a world that has developed the Scientific Method (as it came to be known only recently) and its odd, sort of creepy, little step-child, rational atheism. To dismiss the invisible realm so casually, I suppose one must first become thoroughly enthralled – or overwhelmed – or jaded – by the material, visible one. It seems awfully silly to sometimes have to make this point by indicating that the vast majority of forces in life are immaterial and invisible, such as viewpoints, opinions, considerations, morality, aesthetics, love, and so on and so on. (Also, and I‘m quite happy to stress this point endlessly, as far as poor observation goes, there is so much more to reality than we will ever know that we will always, always, have a very limited perception of it; discovery runs on an infinite scale, after all.)

Moving along. Our early ancestors most likely didn’t see the world as clearly divided into the subjective and objective, as per the Enlightenment. They seemed to have lived in it in a completely different way, at least from what I can tell from the many accounts I have read of tribal peoples as encountered by Western scholars during the past five hundred years. (In a number of these studies, I couldn’t help noticing how common it was for many of these people to describe westerners as sad and lonely; they apparently thought that this was a very odd thing, what with their view of us all living in a fundamentally sentient and welcoming – albeit very strict – universe.)

The invisible subjective

Magic, though, still exists, of course, because most of life is immaterial, invisible and unmeasurable, again such as opinions and morality, aesthetics, etc., etc. (not to mention the things that go bump in the night, especially those long, dark, dark nights).

Good therapy will treat one of the most invisible things of all: the viewpoint of the individual (as in, a view or judgement chosen by a person about something, not necessarily based on fact or knowledge). Modern psychologists and neurologists locate and identify all sorts of activities in the brain whereby electro-magnetic forces appear to be activated, excited, in said organ (there’s specific terminology for all of the following phenomena, which I’ve left out because I can’t remember it).

For example, some fellow, let’s say, a tennis champ, is in a brain scanner and the technician asks him to imagine playing a set, and then, magically, on the screen, some part of the guy’s brain lights up: “Aha, there’s the part of the brain where tennis gets played!”. The questions are, is that an indicator of a cause? A correlation? What? And remember, the subject had to be asked to think about playing tennis before the light show, so is the technician the primary cause in this case? Some sort of “mind network” maybe? Or maybe the act of tennis is the key. Lord! Where the heck exactly is this point that does all this tennis playing and viewing? Reality and consciousness continue to be the greatest mysteries confronting such professionals today—as they have always been. Mysterious stuff when you get right down to it.

So when you’ve got pretty good therapy going, as per Scientology 1.0.0, you’re apparently going to have the most success by treating the viewpoint of the patient, wherever it’s located, rather than the brain – too many variables there otherwise. What does the viewpoint – you – believe is going on? What’s your view of your life? The better the patient is guided or helped to discover for themselves whatever the truth of the matter is, for them as well as the actual reality of their situation (confusing the subjective with the objective is what’s wrong with most of us in the first place), the more successful the therapy is going to be.

Cosmic viewpoint

I remember reading somewhere that magic is defined as “the unseen hand” and thinking that that was a pretty good definition, depending on how you define “hand,” that is, as an active role in achieving or influencing something. This could apply to the illusionist’s art, but that’s not how to interpret it here. Rather, I imagine a perfectly patterned, well-ordered universe (possibly even innately intelligent) acting as the hand, yet it is so vast and so complex that it appears thoroughly random and chaotic to our extremely limited perceptions.

To illustrate, imagine being on a googol x googol (a googol is the digit 1 followed by one hundred zeroes) light-year square chessboard where you, and every other person on the planet, could only measure one picometre (one trillionth of a metre) square of it. All the while, an army of giant grand-masters is continuously and endlessly playing round after round of blitz chess on it. It would appear not only random and chaotic but also meaningless if you believed that what you could measure was all there was to reality. And if you are particularly insistent upon this “meaninglessness,” you’ll become a determinist, the go-to ideology of the devout materialist.

The funny thing is, no one can “prove” one or the other, so what’s actually on the table is your viewpoint, your consideration, and your opinion, and how that assists you. If your opinion leans towards the materialist or the nihilistic, then how does that serve you? Should others avoid you? Probably.

Woo-woo

However it’s viewed, ideas about magic played an important, though accidental, role in the popularisation of Scientology 1.0.0 in the 1960s. Back then, American youth were rejecting the society created by their parents and looking elsewhere for answers, and one of these areas was magic.

When I was a callow youth, I became impatient with the kind of talk that had become commonplace among the newer Scientologists about their special magical knowledge and supernatural abilities. Maybe there is nothing wrong with that, but this unsophisticated chit-chat seemed to my young mind to be developing into a concomitant decrease in critical thinking. With rising levels of incompetence in society, deteriorating constancy, and, perhaps most ominously, the enabling of many bad actors (such as the countless louche and disreputable types who commonly pray upon the more credulous, of which we had more than our fair share), it appeared I might have had a point.

Actually, I didn’t have a problem with woo-woo; I just didn’t want it to supplant objective reality, something that’s really important to children trying to grow up. Objective reality is important because it helps children distinguish between what is real and what isn’t.

Woo-woo is a term coined by James Randi, a well-known sceptic (1928–2020). Basically, it means a confusion, or a contrived collapse, between the subjective and objective realms. By “contrived collapse,” I am referring to the manipulation of this confusion by people like Mr. Randi’s arch-nemesis, Uri Geller. (He did not psychically bend all those house keys and forks; it’s a version of an old illusionist’s trick; anyone who can actually bend objects with their mind would not be messing around stupidly with flatware and appearances on national television, trust me.)

Anyhow, woo-woo is fun sometimes, but I did get quite impatient with it if it seemed to displace useful good sense.

So one day during dinner with my dad, I complained about this by blurting out grumpily, “Where’s all this magic everybody keeps on about?!”. He looked astonished and then asked me, “What magic?” I explained. Then he asked, “You don’t see the magic?” and I said, “No!”. “Well, come on now! What sort of magic are you talking about?” I thought for a second and said, “Such as seeing through walls and levitating things, I guess.” He said, looking even more incredulous, “You can’t levitate things?” and I said, “No!”. He looked further perplexed and asked, “You can’t levitate those?” indicating the salt and pepper cellars on the table between us. I indignantly and emphatically said, “No!” “Really?” he said. “You can’t levitate those salt and pepper shakers?!” Harrumphing, I got up out of my chair at the end of the table and made a great show: “Well, not unless I get up like this, go over to them like this, grab them with my hands, and do this!” jerking the shakers dramatically up in the air. Dad looked at me then, smiling, and said, “And that’s not magic?” We had a good laugh.

Now, he was just having a bit of fun there, but the truth was his point. What’s magic, after all? What’s the ultimate source (as in cause) of anything? After that exchange, I began experimenting a lot with movement and thought. You move your arm up. How did that happen? Where did that come from? Where did the idea, or the thought, of moving your arm come from? Think of a rose. Why a rose? It could have been, say, thinking of a chair or the colour blue, on and on. I was only a teenager, after all, but still. I eventually came to see that it’s a deep, deep mystery where anything comes from and that there is a lot more to attention and reality and its direction—how the former influences the latter—than what I had been assuming.

Anyway, those who actually have spent any considerable time consciously alive, really alive and open, will eventually begin to perceive complex connexions in the world and, possibly, even ways to influence them beyond what would seem normal, if only subjectively at first (change your mind = change the world). Hopefully, while always being mindful not to confuse it too much with the objective realm.

Another way to look at this may be as Clarke’s third law, which states that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. This is probably because, as mentioned before, most natural phenomena have always been (and always will be) hidden from us. I mean both the principles and the workings, for there are an infinite number of things to be discovered. Amusing fact, did you know, for instance, that in the early 1600s, natural philosophers (as early scientists were called back then) all thought mice appeared spontaneously in hay? That was only a few years ago! (I can hear some scoffing at the idea of infinite knowledge, but I assure you that if you ratio all known things against all yet to be known, the answer will always be 0, as in nothing – this is why truly wise people often claim to know less and less as they gain more information.) This view of Mr. Clarke’s, though interesting, is actually off point, but it gets referred to so much that I thought I’d mention it.

Placebo effect

The placebo effect, such as people getting well despite injecting distilled water and taking sugar pills, is more magic!

Sadly, though, that too can get out of hand and become strangely twisted. Millions of people are happily marching around at the very time of this writing, wearing masks, and swearing that they’re alive today because of them. This is a great example of “magical thinking”—the belief that unrelated events are causally related despite the absence of any plausible link between them.

Still, there is the placebo effect.

Responsible magic

The really important thing I’d like to say about magic, however, is in reference to the real deal.

Magicians can gesture or wave a hand, and something at a distance can appear (without mirrors or invisible strings), speak to the spirits and have them speak back, walk through walls, levitate salt cellars, and so on. Well, I’ve personally never experienced or seen this sort of thing, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t or can’t happen. In my view, the current discussion, particularly in relation to Scientology, should focus on the appropriateness of this type of magic. In other words, responsible magic versus irresponsible magic.

This is where I must bring up Goethe’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (brilliantly played by Mr. Micky Mouse in the famous movie Fantasia). Essentially, the apprentice loses control of the spell because he is not yet a master sorcerer, but my preferred reading of the poem is that he would only have attempted the spell because he was lazy. This is what I’m referring to when I mention irresponsible attempts at magic: the desire to do what I call an “end run” around nature, often in an effort to avoid effort (as in work). Life without useful, productive, and valuable work isn’t worth much. The amount of imagination, thought, skill, blood, and sweat that goes into art and inventions, to name just a few examples, demonstrates “responsible magic”.

There are levels of responsibility in all things, and responsible magic is in a whole different league than those who need the physical universe to be different than it is. I mean, we share this universe and even the things you “own,” you don’t actually. You have property, sure, and nobody else has the right to use it without your permission or due process (depending where you live), but all this stuff is actually made up of particles that make up the whole physical universe. If someone got to move these particles around willy-nilly, wouldn’t that be a cheat, even dangerous? Or even a kind of theft? Sort of like someone sneaking into your home at night while you’re asleep and rearranging your sock drawer whenever they please. I’ve heard this power expressed by people who “change” or “create” the weather (may my friends who believe these sorts of things forgive me), which always made me wonder about their hubris: that incalculable trillions of vectors get switched around because they wanted sunshine on their wedding day. To be fair, there is such a thing as prediction, which is when you just know how something’s going to go, after all – and that, that right there, is magic of a very high order. If more of us paid more attention to what we just know – really know – with no second guessing and whatnot, then we’d be living in a whole different and much improved world.

I suppose the above might be too harsh a view. I mean, I don’t exactly get to say what’s magic and what isn’t; outside of my own opinions, it’s a hard thing to know. And, besides, to be equitable, this sort of “magical thinking” may be pretty harmless for the most part. On the other hand, the important question in my mind is, where does it stop? This is why I have always preferred a small republic form of government over any kind of democracy, because the majority of us just can’t reason as well as we might, especially at that level; not yet anyway. I say this because of the propensity of the majority of voters to support regimes that offer them “free” stuff like food and money, and there are few better examples of magical thinking than that. Most of us are pretty good at thinking about the things that are local and intimately perceivable, such as our own homes or neighbourhoods, but getting our wits around bigger systems doesn’t seem to be our forte, nor should it be particularly… yet. As far as critical thinking goes, it’s a complicated skill that needs to be learned, and personally, I just haven’t met many people who are very good at it without training. (Not that I’m so great at it either, I’m just saying.)

Speaking of magical thinking, its use in place of reason when reason would be much better served. Children, usually ages three to six, quite naturally default to this way of seeing the world as they have yet to learn how to think. One is born with all the feelings and emotions under the sun, but thinking correctly is a matter of education, and it’s that training that gets these elemental forces under control. (Watch out for that six-month old that you think is just crying, it’s probably actually an expression of a level of rage and frustration that would make Hitler blush.) A lot of adults, like the Boomers and many of their offspring, get caught up in magical thinking. This may be because it’s drummed out of them during childhood instead of being integrated into higher levels of thought and cognition.

It’s possible that it’s too late for many adults today, but if we get around to properly restructuring education, we might try to incorporate magical thinking (along with their vital imaginations) into all the more sophisticated types of thought that followed the hunter-gatherers. And then, who knows what might be accomplished?

That being said, just one little extra stab at emphasis here. It is no coincidence that there is a relationship between magic and wonder (and awe). As I believe I mentioned previously, I think wonder is mostly lost to adults in these modern times, and that is a very, very serious problem in my view. I don’t know, it could be just me. It takes a lot of courage (another invisible force) to live properly in the world. Life, after all, is not for the timid. Therefore, I think wonder, because of its connexion to faith (yet another invisible force), cannot be experienced much by the faint of heart, for they’re too busy worrying; to lose the wonder is to risk the death of all spirit, especially that vital quality, courage. I think we miss this point today, possibly because we equate courage with force (military, police, emergency personnel), which can sometimes be the case, but it’s better to equate courage with wisdom, and there is no greater invisible force than that.

Myth

Speaking of courage and wisdom, the other thing that we did and still do is tell stories about being in the world. Life’s “whats and hows,” I suppose you could say. This is another rung in that ladder that got kicked out in the 20th century, so badly so that it took a movie, Star Wars, to help put it partially back. It’s still pretty much a dead subject, though, and it really oughtn’t be.

A typical definition of myth: a traditional story, especially one concerning the early history of a people or explaining a natural or social phenomenon, and typically involving supernatural beings or events. From Late Latin mȳthus, from Greek mŷthos “story, word.”

Maybe a better definition, if I may make so bold: myths are stories that describe the history of life on Earth and the archetypal human experience of being in the world including the “call to adventure” and descriptions of heroic (successful) behaviours such as persistence in the face of adversity and how one may become connected or disconnected with invisible forces and the Infinite.

My thoughts: Myths are original pattern recognition at a much higher resolution than any algorithm currently available. They are the accumulated wisdom of thousands of years of trial and error, and you must have these guides because they contain more information than can be learned in the span of one life. To live properly, you’ve got to know where you are – what sort of world you’re living in – and what you should do about it. Not knowing these things can make the world more dangerous than it needs to be.

For working out what we’d need to know about our world, we ought to first have a pretty good idea of the game itself, what sort of board it’s being played on, and what the game looks like when you’re winning or losing.

Orientation and identification

The first step in life is to figure out where you are. Scientology 1.0.0 refers to not knowing where you are, not surprisingly, as “confusion.”

Confusion refers to being dislocated in space as well as time; a total, or near total, failure to recognise any pattern(s). It is surprising, when you investigate people from this standpoint, how many of us really don’t know where and when we are. (For instance, a lot of what is happening politically right now in the U.S. is perpetrated by activists who think it’s Selma in the 1960s.)

Then you need to figure out how to be in the world that’s been revealed. This requires that you figure out what and who you are. Every person has to make these two discoveries for themselves at some point in life. Not knowing what and who one is will stick you in a kind of deadness.

Knowing what you are is essential for becoming an active and necessary player in the world. If you don’t come to realise that you are in fact an essential character on this wild and woolly game board, then whatever you do will be as ineffective as the non-player characters in video games, or worse, a cypher.

After that, you need to figure out who you are, which is to say, your specific role and all that entails. These steps go far beyond, “My name is Jane Smith,” because the next question is always, “Well, who’s Jane Smith?”

Perhaps I’ve made this sound too simple, but it’s actually pretty involved stuff. I mean, how many people today still don’t know where, what, and who they really are?

So. Myths are stories about the origins and nature of the world (i.e., the Enüma Eliš or Hesiod’s Theogony) and stories about being in it (i.e., the Epic of Gilgamesh or the Labours of Hercules). These stories were key to relaying that there is a certain order in the world, a world that would otherwise seem too random, as opposed to its disorder (the capriciousness of the gods), and they were crucial in laying the groundwork for other necessary kinds of investigations of reality yet to come: philosophy, psychology, and so on. We got through today because these stories, always multifaceted and symbolically dense, were so true in describing the world as it actually is. Hooray!

Quite a few of the main themes, though, seem to be intrepidity and courage; the way up is the way forward; there is no room for mice-people or soy boys. A world that is managed with the right attitude and in the right way is one worth living in.

Through much telling and retelling (and a lot of living), these ideas would be developed the world over, the themes being almost identical no matter where they were told.

As for us in the West, many examples come from Ancient Greece, written down by guys like Homer. The Iliad and the Odyssey are two of the best descriptions of the human condition ever produced in the West. These two works are perhaps the most foundational of all in the Western canon, a perfect synthesis of art and historical fact. For instance, a fellow named Herr Heinrich Schliemann excavated Troy in the 19th century, proving that what experts thought of as pure fiction was as much historical record as it was imagination. The bottom line is that without Homer, there would be no Western civilisation.

Possibly, I should make a little note here: Western civilisation is often referred to today as “Anglocentric,” “Eurocentrism,” or “Western-centrism.” But watch out; this is an example of politically correct newspeak. The fact is, without invalidating any of the thousands of other cultures, Western civilisation and its ideas are the dominant ideas in the world today because they developed individualism and the resultant explosion of technologies we wouldn’t recognise the world without.

Anyway, to continue. Before and since Homer, there were, of course, many myths telling one particular tale: heroes and their adventures. Heroes have to confront all sorts of challenges, the way that when we do the same, life becomes a damn sight more interesting (I think we’ve all known our fair share of Labyrinths, Hydras, Gorgons, and dragons; whether we faced up to them, though, that’s the question). No matter who you are or what station in life you find yourself in, you will be met with multiple trials and challenges, which may be broken down symbolically into various types and categories. Read these hero myths with care and much could be revealed.

Many of these myths could also be metaphors – although metaphor isn’t quite the right word – for the ultimate story too, such as confronting the shadow monsters in our own psyches. Like a hero descending into the underworld, we can attempt to find what Carl Jung called “the treasure hard to attain” – and by slaying the dragons residing therein, we might repossess our very own souls. This sort of adventure is the most harrowing and most difficult of all. Because so few of us can do this – and of those who attempt to do so, so few are successful – most of us just learn to “manage” our demons. Or dope them, and ourselves, into oblivion.

A really good read is The Hero with a Thousand Faces, by Joseph Campbell. What he goes to show are the similarities, the world over, of mythic tales and the repeated arcs that they take. These are his observations about the stories told again and again about the basic circumstances of man in a very definite world, regardless of culture, and what happens when we take it on in such a way as to obtain the best chances of survival and success. Although many are stories about the environment, nature, our interaction with it, and the kinds of spirit that win or fail, the most important tales are discussions of ideal being, the ideal man, such as with the Osiris/Horus composite or the “mega-man” – King of Kings – as discussed in the New Testament (although Jesus was clearly an historical figure, he is much more than that). It could be argued very strongly that these descriptions of this ideal led directly to being able to eventually describe, or delineate, the sovereign individual, which, when given definition, gave us the American Experiment of 1776.

However, the debate about how to define this ideal has significantly waned over the past century or so. To such an extent that today, too many of us almost invariably use the wrong measurements for being, whether it is as an individual or a group (as an example, using net worth, gross income, or how much stuff one has).

Anyhow, as it is commonly understood, myth doesn’t get discussed a whole lot in Scientology 1.0.0, although many myths are referenced in lectures and so on, but the mythic “ideal being” very much does, because the courage and fortitude to stand up straight in the world are foundational to any true journey of the spirit.

Connecting the dots

So, the hero idea has been under siege to the point that the word is now pretty meaningless. I mean, today, anyone who can put a little mist on a pocket mirror is a “hero”; it’s like the worst kind of suffocating, smothering mommy archetype has taken over the world (every mother’s “little darling” is a hero in her eyes).

Personally, I experienced this murdering of the hero while going to school, where myth was taught mostly as tales from a very, very distant past. To be fair, this was how it was being taught to 8-year olds, and had I stayed in school (this was in England), we probably would have gone on to investigate these stories in greater depth, England still being very connected back then to its Brythonic roots and later Ancient Rome and Greek culture. Looking over the high school curriculum in the United States, though, revised (read: sabotaged) in the 1950s, it was clear myth was being taught as the interesting, although quaint, blather of primitive peoples. (Much later in 2017, talking with a friend’s daughter who had graduated from Oxford University, I discovered, whilst discussing Beowulf, that she had been taught to believe fervently that the Western myths are the dangerous delusions and calculated propaganda of an all-white patriarchy designed to crush the proletariat, exploit women, persecute non-gender specifics while colonising and enslaving all people of colour – whew!)

These days you could maybe take courses in astrophysics, biology, ethics, and behavioural psych 101 to try and learn this stuff about correct being, I don’t know, I didn’t have much of a formal education. But, despite being probably futile for that purpose, those subjects seem a bit dry to me – especially if you didn’t also study mythology, because that’s where the music is.

So it’s a bit of a problem that today, the term “myth” mostly means “untrue.” Indeed, and to try to be fair to the educators of the past and present, it is very true that after many translations and transliterations, and after multitudinous, ever changing cultural paradigms, many of these tales are somewhat baffling; what possible use could they have today? But here’s an observation: Many people who are otherwise unaware of, or could care less about, our mythic underpinnings are huge fans of things like The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars and the Harry Potter adventures, proving that these stories remain as active and alive as they ever were and still play as vital a role as they ever did. My thought is that this is so because these movies and books are new and modern, and therefore recognisable as retellings of our most ancient observations. Even so, we, as a culture, should still link it up and make the connexion.

Man is fundamentally an intrepid species of keen intellect and faculties, and it’s these tales that guide and inform him. Luckily for us, Joseph Campbell and many others following him, plus many artists, have gotten onto this problem one way or another, and myth is back in the conversation somewhat. This is one of the deep wells I personally hope we will all be drawing from more and more going forward.

Conclusion

To sum up, after art, the divine embodiment of the creative urge, there were early forms of religion, the recognition of the uncompromising forces of existence. Then came magic, negotiation with invisible forces, then myth, ways to properly take on the world.

Things are building up.

Next: Mysticism

One response to “Magic and Myth”

Magic; intent stylized and protected with a bit of obfuscation.

Scientology; intent cleaned and drilled?

Sort of similar to the difference between art and engineering, but still the same fundamentals.

We fill the gaps in our understanding with comfortable ideas, myth, until we progress.

LikeLike