The Wild Mind – Part XVIII

Scientology 1.0.0 – chapter 25

“All men’s miseries derive from not being able to sit in a quiet room alone.” — Blaise Pascal

There might well be a pandemic raging in the world, but it would seem it is not so much of the body as of the mind. Mental health has possibly been the most serious problem facing mankind these past seventy-five years or so, ever since the advent of the Third Industrial Revolution, a development that, it would seem, we have yet to learn how to manage properly.

It is also quite possible that most other recent and ongoing systemic failures, outrages, and tragedies are, for the most part, mostly symptoms of this difficult mental situation.

Hard science versus soft science

Once again, I might be in “everybody already knows” territory, but for the sake of future arguments, here goes.

Hard science and soft science are informal terms used to compare scientific fields on the basis of perceived methodological rigour, exactitude, and objectivity.

Hard science is a description of the physical sciences.

Hard science is “hard” because, as practiced, it increases in reliable data that is founded upon facts or substantiated information and, as it progresses, proceeds only with already verified knowledge. Hard science results in improved integration and organisation of data and an increased ability to detect errors. It also results in an increase in the complexity of the subject because, as more is learned about anything, it reveals additional things to know.

Hard science got us the first, second, third, and now fourth industrial revolutions (“evolutions” would be more correct).

Soft science is a description of the social sciences.

Social science is one of the branches of science devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies.

But to understand societies and relationships, you’d need to know something about human beings, yes? Science, though, at least as it stands today, knows almost nothing about people, thus ‘soft’ actually means “imprecise.”

Psychology (the scientific study of the human mind and its functions, especially those affecting behaviour in a given context; from Greek psukhē ‘breath, soul, mind’), is the field that should know all about individuals.

So, talk about “soft.” Although man has reached a level of miraculous technological advancement through the hard sciences, he hasn’t advanced much in the wisdom department, which would be the actual business of the social sciences, especially psychology. Indeed, possibly because of the near total absence of methodological rigour, exactitude, and objectivity in this category of science, it could even be argued that, as a result, we are currently experiencing an alarming decrease in what hard-won wisdom has been attained over the past millennia, especially in terms of our systems, such as common law, property and privacy rights, free markets, money (as in actual money, not the utterly unstable rubbish we use today), and representative government, all of which are grounded in the immutable principles embedded in Natural Law.

These systems are often poorly understood and historically do not fare well in democracies as they are complicated and thus fragile in the hands of individuals whose social morality is traditionally limited in scope (as in, people will unthinkingly vote for freebies). As a result, instead of finding out why our money, for instance, gets more and more useless, we all run around like hypnotised mice fighting over which hapless soul is going to disgrace the presidency next, just so long as they promise us “change.”

Evil, which is always irrational because it is unnecessarily destructive, is not usually proactive; it’s opportunistic (I will give a full description of “evil” in a future article, but for now let the definition be those persons and their actions that are harmful to the survival of individuals and society). Like black mould, evil can only get a hold on people or societies under the right conditions. Besides parasitising our tendency to be greedy, as soon as any emergency crops up (which they do even when we are not creating them), working systems, being poorly understood, can get easily circumvented or distorted by bad actors. This can have a cascading effect as it upsets people on top of the upset already caused by the emergency (whether fake or real), and whatever mental fissures (irrational behaviours) already reside within us begin to manifest to a greater degree, snowballing into the inevitable breakdowns all civilisations, even the better ones, suffer with such depressing regularity.

If we don’t know the causes of irrational behaviour, then societies and all those hard-won workable systems are always and forever at risk of being torn down, or, at least, so altered that they can then be easily co-opted by tyrannies—totalitarian systems that seek total control over everybody—always for “our own good,” of course.

So, what might have happened that science has fallen so far short in the social sciences?

Original hypothesis

“Man is basically bad.” Or “irrational,” which is how psychologists put it.

With the rise of psychoanalysis in the 19th century and through the development of and experimentation with hypnosis, a dark, shadowy element of the human psyche was more explicitly revealed: the “unconscious mind.”

The Austrian neurologist and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud developed the concept of the “unconscious mind” (which is already a misnomer because it is obviously not unconscious—rather, it is a conscious level of mind that is usually unavailable to the analytical, that is, conscious level of mind). Later, Anna, his daughter, widely promoted the theory.

The unconscious mind consists of “ideas and drives that have been subjected to the mechanism of repression of anxiety-producing impulses, usually experienced during childhood (per Freud), that are blocked from conscious awareness but do not cease to exist.”

To restate, there are apparently these ideas and drives that can continue to exert constant pressure, acting almost like “commands” upon the conscious mind of the individual, often resulting in bizarre or illogical behaviours.

There was an additional theory: that this mind, the unconscious mind, is the foundational mind—a mind that, because it lies “underneath” the thin veneer of “civilised” behaviour, must therefore be more basic. In other words, the unconscious mind got “located” at the root of human personality.

This belief was felt to be proven by observing how easily people’s sociability could be stripped away, returning them to the base instincts of tooth and claw. It perhaps derived from the “man from mud” theory: the idea that man accidentally arose out of goo, passed through millions of years of cellular and animal forms, eventually evolved into apes, etc., etc., and then somehow got a big brain that made him smarter than animals.

So, the theory could be reiterated as follows: man is capable of rational thought, yet being basically an animal is fundamentally irrational. Or something like that.

It followed that since this unconscious mind is basic, permanent, and irrational, the only solution would be to “help” people by getting them to first be aware of this animal mind and then training them into acceptable social conduct, sort of like one can do with… animals. In other words, get people to suppress their repressed irrational emotions and conform to societal norms (norms as dictated by self-appointed experts who, we hope, are somehow not irrational).

So. The big idea was to change man from being the shaper of his world, which is what he actually is, to being man as reshaped by the world. Or, actually, as shaped by the oh-so-rational, somehow magically non-animal custodial elites. Uh-oh. (This is eerily similar to “behaviourism,” which is: human and animal behaviour can be explained in terms of conditioning without appeal to thoughts or feelings, and that some mental conditions are best treated by altering behaviour patterns. Altering? How? Double uh-oh.)

Also strange: wasn’t the problem repression in the first place? How is repressing these repressions going to work? Isn’t that called “doubling down”?

Anyway, no actual cures were developed from this hypothesis.

On a truly sinister note, though, for some other self-appointed custodians, understanding the unconscious mind this way would lead to techniques that would control and manipulate these dark urges on a grand scale. This, in turn, could have perhaps disincentivised the development of any real cures.

The pathology business

You cannot exploit madness for purposes of increasing your influence or growing your bottom line without it spreading. Spreading insanity, I mean. If keeping people crazy and indeed making them even more crazy is “good for business,” then why cure it?

This “unconscious” mind, now isolated and studied, was utilised to brilliant effect by Freud’s nephew Edward Bernays (1891–1995).

Using Freud’s theories, Bernays was able to practically invent the field of public relations as well as elevate propaganda to such heights that today one need only push a button or two and a majority of us jump to obey. This is ably described in the book by Edward Mandell House, Philip Dru: Administrator, wherein the stimulus response apparatus, apparently a feature of the so-called unconscious mind, is triggered into action. This mechanism is described in Hegelian dialectics as “problem, reaction, solution.” For example, create a problem (COVID), get a reaction (mass fear), and have the public demand solutions (lockdowns, more government, loss of civil liberties). It’s an old, old trick, but with the use of modern mass media platforms today, it’s a cinch.

The degree to which this unconscious mind could be manipulated is the subject of Bernays’ book, Propaganda, and his essay, The Engineering of Consent, which should be read by everybody because much of today’s insanities as well as a fair bit of the horrors of the past 100 years can be traced in no small part to this deplorable use of psychoanalytic theory. For instance, Joseph Goebbels, the Nazis’ Minister of Propaganda, was a master pupil of American public relations and used it to great effect on the German people.

(If anyone wishes to study consumerism, politics, and sales techniques, then they should start with Freud and work their way through Bernays and so on.)

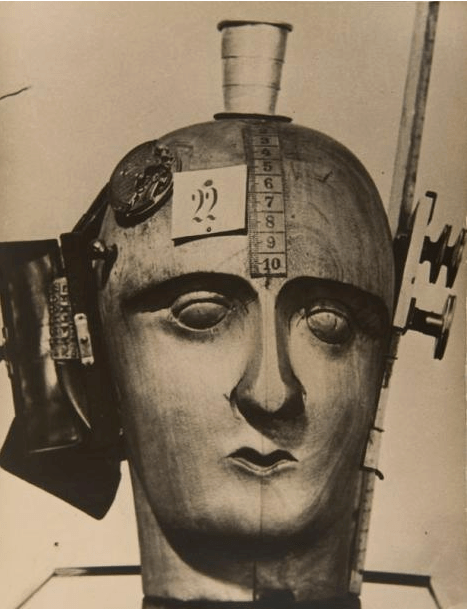

Clockwork man

With the finalisation of the acrimonious divorce between science and religion in the 18th and 19th centuries, science more or less lost the plot. That is, man’s eternal struggle is not just how to survive physically; his bigger struggle is between good and evil, right and wrong. Recognition of a greater power is what leads him to higher ground. This is the vast realm of both objective and subjective realities.

Science has mostly been successful in the objective world. Compared to the subjective, though, the objective world is exceedingly simple and is readily reducible to its component parts for the purpose of study. Modern science, originally in the hands of Newton and Descartes and for nearly all scientists that followed, were reductionists.

Reductionism is the practice of analysing and describing a complex phenomenon in terms of its simple or fundamental constituents, especially when this is said to provide a sufficient explanation.

This is useful for beginning a scientific inquiry but is a terrible place to end up, especially if one is studying people. (A great book that covers this subject is The Turning Point: Science, Society, and the Rising Culture by Fritjof Capra.)

By means of reductionism, the physical universe can be seen as a clock. If you pull it apart, you can figure out how it works enough to discover and invent wonderful things, such as better clocks.

If you break people’s bodies down into bits, you might develop some medicines, but you can’t reduce the mind sans the soul and expect to get any cures; it’s a hell of a problem! Religion doesn’t do this because man is not a machine.

It’s a poor analogy, but religion doesn’t dissect the mind (minus the soul); leave all its bits and pieces laid out on the cold laboratory slab and expect anyone to properly understand him (see chapters on religion). But science tries to do exactly this with psychoanalysis.

Perhaps it went something like this: first, get rid of the woo-woo stuff: God and souls and all the invisible bric-a-brac (“hand me that scalpel, nurse”). Then dice up the mind/body (which is which, no one knows) into libido, ego, and super ego; conscious and unconscious, etc. And then hold up the unconscious mind and say, “Behold! The incurable tumour of human behaviour revealed!” Then go home and celebrate with a martini or two: “Our work here is done.”

Science isn’t science if it gets poor results and then says, “There! Man is stuck with his irrationalities, and there’s nothing more we can do about it.” (“Except exploit the living daylights out of him,” say the ad men, propagandists, and govco [government/corporate] elites.)

Imagine if a scientist set out to discover the actual shape of the Earth, looked around from horizon to horizon, and happily exclaimed, “The Earth is flat!” (and then got back in his little boat and assiduously avoided the edges for fear of falling off). Not much of a scientist, you’d say. Well, that’s more or less what’s happened with psychology: it stumbled over this very real unconscious mind business and, failing to do much with it, assumed that it was permanent and basic.

To be fair, though, psychologists did set about measuring how it behaved.

Psychometrics

Famous such studies are: the Asch experiments, which discovered most people are easily manipulated to lie; the Milgram experiments, which discovered that most people can easily be made to do bad things to other people; the Hofling Hospital Experiment, which proved nurses could be easily encouraged to overdose their patients; the Stanford Prison Experiment, which proved ordinary college students could easily be turned into sadists; the Third Wave experiment, which showed how easily high school students could be turned into Nazis; and Jane Elliott’s “Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes” exercise, which illustrated how easily eight-year-olds can be turned into racists.

To me, more alarming was another experiment. For 15 minutes, participants were left alone in a room in which they could push a button and shock themselves if they wanted to leave. 67% of men and 25% of women chose to shock themselves rather than just sit there quietly. For just 15 minutes! Lordy.

Many accurate and useful psychometrics have also been developed, such as Gordon Allport’s (1897–1967) trait theory, as well as pretty extensive diagnostics like the Psychopathy Checklist, assembled by Robert D. Hare CM (1934–), for instance, as well as studies like Paulhus and Williams’ “dark triad”. These are especially useful in teaching how to spot the bad actors in society.

By the way, that Milgram experiment? It required that the “doctor” directing the subject dress the part; that is, look like an “expert.” It’s possible that our high rates of mental illness prevent people from recognising or accepting any existing technologies for healing the mind and spirit because the hucksters advocating unworkable technologies (such as medicating everything) look exactly like experts. (It might have been in this same way that exercise, sunlight, zinc, vitamin D, and hydroxychloroquine were successfully suppressed in favour of dangerously experimental and unworkable alternatives a short while ago because the “experts” deriding them, such as Anthony Fauci and Bill Gates, appeared endlessly on our screens and everybody knows only experts get to be on TV.)

Pseudoscience post Freud

The basic hypothesis remained intact: the unconscious mind is fixed and basic, but new tactics as to how to deal with it eventually emerged.

Wilhelm Reich (1897–1957) was a student of Freud, but unlike Freud and Anna, Wilhelm saw expression rather than re-structured repression as man’s way out. Rather than repressing all the dark and dangerous emotions and urges, let ’em out!

This new approach became widely popular during the 1960s as many psychologists followed Wilhelm’s lead, including Arthur Janov (1924–2017), famous for the primal scream. Years of dramatising the contents of the unconscious mind, though, not only produced few cures but instead arguably contributed to the increasing degree of narcissistic-like self-absorption so commonly attributed to the Baby Boom generation and which has only increased with those that have followed.

I should state here that not all psychologists adhere to the “man is basically irrational” school, but most in the field do. This is perhaps because psychologists are almost always atheists. Atheism has the distinct advantage of simplifying things (reductionism, again) to the point where very little of what is truly important and vital remains and thus needs to be studied. Simply label religion and God as pathological, and voilà! (And then off home for more of those delicious martinis.)

On the other hand, there do exist some methods that, as practiced, often show an improvement in certain cases, such as cognitive behavioural therapy and exposure therapy, as well as some useful training exercises such as those described in Dr. Ellen Langer’s book on mindfulness (not to be confused with how this term has been watered down in pop culture but is rather based on the astute Eastern observation that being present in the present and mental health are inextricably linked).

As for other approaches, psychiatry (which has long since become a sales subdivision of Big Pharma) sees irrationality as the result of “imbalanced” brain chemicals. If this is true, then why not just invent a pill and everybody is magically “good” (less aggressive and even more malleable), like Huxley described in Brave New World? Well, considering all the hundreds of chemicals that have been used to experiment on the human population over the past seven decades (such as would probably make even the Nazi “doctors” blush), you’d think we’d have developed one by now.

But no, no pill, nothing. Crickets. Despite the temporary alleviation of certain symptoms of mental illness (before a stronger dose or whole new cocktail is needed), no one gets cured of anything. Psychiatry is indeed a very soft science, so soft it’s downright peach fuzz, just like the Flat Earth “scientist” who’ll never discover anything, least of all the New World.

It’s been well over a hundred years of psychology and psychoanalysis and primal screaming and drugging, and we’re not getting any better, at least not as a society, all because of a stall hardly anyone noticed: few actual cures, possibly because so many practices are predicated on a faulty theory—a theory concocted, probably, by people who don’t actually like people (Freud was a notorious misogynist and something of a misanthrope).

So. What if, (just spitballing here), what if the key to actually curing people of mental illness lies in an opposite theory?

Man is basically good

My father’s theory is the Eastern theory that man is fundamentally spiritual. He expressed this idea in others ways such as “man is basically good” (there’s much more on this that I’ll cover later).

I can hear the same cries he once heard: “Absurd!” “Preposterous!” “Crackpot!” True, it’s a proposition considered by many people to be extremely, possibly even dangerously naïve.

And I get it. How could one explain all the horrors of history, or all the human tragedies we see on the news every day, except by the fact that man is basically crazy, fundamentally irrational; in a word, bad? It’s clean, it’s simple, it’s even pristine. But be careful, because it also means that if you want to do terrible things to people it’s okay, it’s okay, because they deserve it! That man is basically bad is exactly how evil people want you to think and many of us have fallen for it.

The counter-argument, though, is, how can one explain all the good things then? If man is so bad, how is it that we’re still here? It seems we’d have bumped ourselves off long, long ago. Look, what’s the goal of evil anyway? Swarms of expendable slaves run by a few experts, of course. It’s already proven to be unsustainable, so talk about naïve.

Maybe the basic mind isn’t the unconscious mind at all. Maybe the fundamental mind is actually a mind that is much more conscious; maybe, just maybe, the fundamental, foundational mind is a mind that is not just conscious but potentially superconscious? Not a mind at all, in fact, but spiritual?

Possibly, if man is basically good, he shouldn’t have to repress anything at all because the “unconscious” mind is not inherently bad, insane, or irrational, no matter how hard some of its contents may be to confront; maybe this mind is in fact good because it actually only holds information and it is only “bad” or “evil” because one can’t see it or use it. In Dianetics, it’s this vast vault of vital knowledge which, when untapped, unviewed, or ignored, only appears to “act” against one.

If you can perceive something, you might have a shot at controlling it or using it. Get this hidden mind out and into the open where it can be seen; no repression, reconditioning, or reprogramming is necessary. And once seen, possibly it can be used. Or not.

Actual science again

Science is the systematic study of the origins, structure, and behaviour of the physical and natural worlds through observation, experimentation, and the testing of theories against the evidence obtained, resulting in improved survival by means of advanced technologies.

Hard science has been fabulously successful, social science not so much.

Perhaps it’d be better if these social sciences were less soft and more devoted to the development of hard (workable) technologies of mind and spirit that resulted in actual cures that would in turn strengthen our successful social systems—and help us become wise enough to keep them safeguarded 24/7.

This huge step, of course, will require new hypotheses that yield better results, such as: man is basically good.

Is that naïve? Well, maybe. But I don’t see us going too much further in the physical sciences without mankind becoming wiser, and that won’t happen if he’s already been given up on with soft science.

7 responses to “Science, continued”

Beautiful article Arthur!

I appreciate you making sense out of your father’s work.

You have reminded me that change for the better isn’t instantaneous.

Martinis may taste good but…

I would love to talk with you sometime.

Matt

LikeLike

I’d like to comment on the current status of Scientology.

I believe David Miscavaige is a miscreant who is ruining Scientology. From getting to know several people who worked close to him, he fits into the “Man is basically bad camp”.

I would like to help bring back “my Scientology”.

LikeLike

Thank you again! Each time I read your articles its fresh air. And may I say they are more logotechnic [compound Greek word from logos (Λόγος) = speech/word or even Reason etc. and Techne (Τέχνη)] than your father’s.

Beautifully written but powerful indeed.

LikeLike

Techne meaning Art

LikeLike

Techne means Art in Greek

LikeLike

Of course your father had another role and that role was heavy enough! Good morning from Athens!

LikeLike

Thank you, Theo. Good morning from California and happy holidays!

LikeLike