The Wild Mind – Part X

Scientology 1.0.0 – chapter 17

“A marveilous newtrality have these things mathematicall, and also a strange participation between things supernaturall and things naturall.” — John Dee

As interesting and constructive as are all the subjects previously covered in the Wild Mind articles, things get especially fascinating with alchemy, particularly if one sees the universe as a product of nous (the mind), rather than the other way around.

Which Scientology 1.0.0 definitely does, sees the universe as a product (more like an expression) of nous; at least in part. It goes beyond that. This is why, along with mysticism and Eastern philosophies like Hinduism, Taoism, and Buddhism, the following is another source of its basic principles

But if things like religion and philosophy can seem irrelevant or confusing these days, alchemy usually gets completely lost in the shuffle, so I hope you’ll bear with me as I try to sketch out a few things about yet another vast subject, using my usual broad stroke descriptions and possibly an oversimplification or two.

Again, alchemy, like all the rungs on the ladder of civilisation, is a precise subject and connected to literally everything. As usual, and for the most part, all I’ll try to do here is indicate how terrifically significant and important it was, and still is, in getting us all to the good things.

First, some personal colour.

Here, in the West, we entertain a peculiar double standard: we don’t consider a religion to be valid unless it is old, yet we often don’t consider any subject useful unless it is new. Whew! Hard to work with that. I’d guess this is a subconscious response to the fact that we all know wisdom is old but things like science are always improving. In science, newer is often better.

Many old-timers in Scientology will remember that, in the 1970s, there used to be a magazine put out by the Church called Advance. It used to contain articles on subjects like religions and practices besides those of Scientology. Without being overtly explicit, it was indicating that Scientology was both new (its scientific aspect) and old (its religious aspect) by positioning1 it with thousands of years of wisdom.

I don’t know what happened to the magazine, if it continued with or without those articles, but I know that officially discussing esoterica, spirituality, and other religions eventually got mostly dropped in favour of concentrating more upon the writings and lectures of L. Ron Hubbard.

I worked on that little magazine in 1974 and ’75. The writer of those articles used various resources, one of which was a hardbound collection of another magazine previously published in the U.K. called Man, Myth & Magic, which, although somewhat dismissive of man, most myths and all magic, were still interesting because they were so jam-packed, encyclopaedia-like, with articles on everything from Abracadabra to Zoroastrianism. I’d look through those books, and in 1976, the writer Omar V. Garrison gave me a set.

Later, between 1976 and 1979, for a period of about two and a half years, I spent a lot of time with my father, certainly more than we ever had before, and in our chats he would often wonder what I was reading. Well, at one point, I was browsing Man, Myth, & Magic again, and I told him I was very interested in finding out more about those subjects. This was when he began telling me about some of the origins of his own work. I have to say, I was somewhat surprised because, by the late ‘70s, in the culture of Scientology 2.0, that is to say, the institution rather than the subject, little was discussed about the origins of Scientology.

Not that nothing was said; a lot was mentioned about other practices. I mean, they were not much talked about as being connected to or leading up to Scientology 1.0.0; attention was mostly focused on the business of getting Scientology known and used. As a result, at least in my callow eighteen-year-old brain, Scientology 1.0.0 was rather thought of as having hatched, wholly formed, like motherless Athena, from the forehead of her father, Zeus. Boink!

In one of our conversations, my Dad mentioned that, in the 50s, he would reference many of the origins of his work, but by the mid-60s he didn’t so much. Apparently, as the 1950s waned and the 60s were dawning, it was proving less and less helpful to direct any student’s attention to things like Isis cults, the Eleusinian Mysteries, or, even, the Upanishads (the Vedic texts were mentioned a lot). Certainly not to such intoxicating things as Aleister Crowley or magick (as Aleister spelled it).

The 1960s were a decade of extreme experimentation—socially, pharmaceutically, pseudo-mystically, and otherwise (oh oh). Placing these nuggets of ancient arcana before the all-too easily distracted, newly minted TV generation was proving to be an inapplicable diversion from simply learning and applying the procedures of Scientology 1.0.0, which was the main mission at hand. Also, stressing the new and original aspects of Scientology 1.0.0 was a way of attracting such people to it. (No offence to us boomers, but although the times were a-changin’, it was not all for the better necessarily; this was a crowd for which everything had to be new, the old thought to be at best passé, at worst useless. It is not uncommon for the young to think in this way, but this particular batch of children was the largest in recorded history, making them a powerful cultural force. More on this later.)

There are a couple of points that many people online miss in discussing Scientology. Even though some of its ideas have been around for a long time and some of its principles can be found in other fields of study, Scientology’s processes and procedures are original.2 These processes were then able to produce the discovery of additional principles and axioms that had never been previously known. So, it was and still is, for the most part, both original and new.

Anyway, in our conversations, Dad indicated he was expecting people to make all the connexions between these things on their own and in their own time, this being vital in order to fully grasp their meanings, and, by extension, how Scientology actually works. Meanwhile, there seemed little point in sending people off down various fascinating paths without their first getting cleaned up using Scientology therapies, which is what they were there for in the first place. Considering the fact that there were also time constraints and economic considerations (more on this later), this made, and still makes, perfect sense.3 Besides, most of the data and references are all there in his earlier work; all one has to do is make the time to look them up. But then, most people don’t. Make the time, I mean, especially not its detractors.

So, it is not surprising that today, few people know the full extent to which the subject of Scientology owes its existence to at least ten thousand years of wisdom and tradition. In fact, the same can be said for almost the entire Western population in terms of how much we all owe to the past and its towering thinkers and monumental accomplishments. So awful is contemporary education that it’s no wonder that many young people today can’t make the many, many connexions between their iPhones and religion, philosophy, etc., let alone alchemy.

That being said, the following is a brief discussion of the next rung on that ladder of experience and thought.

Alchemy

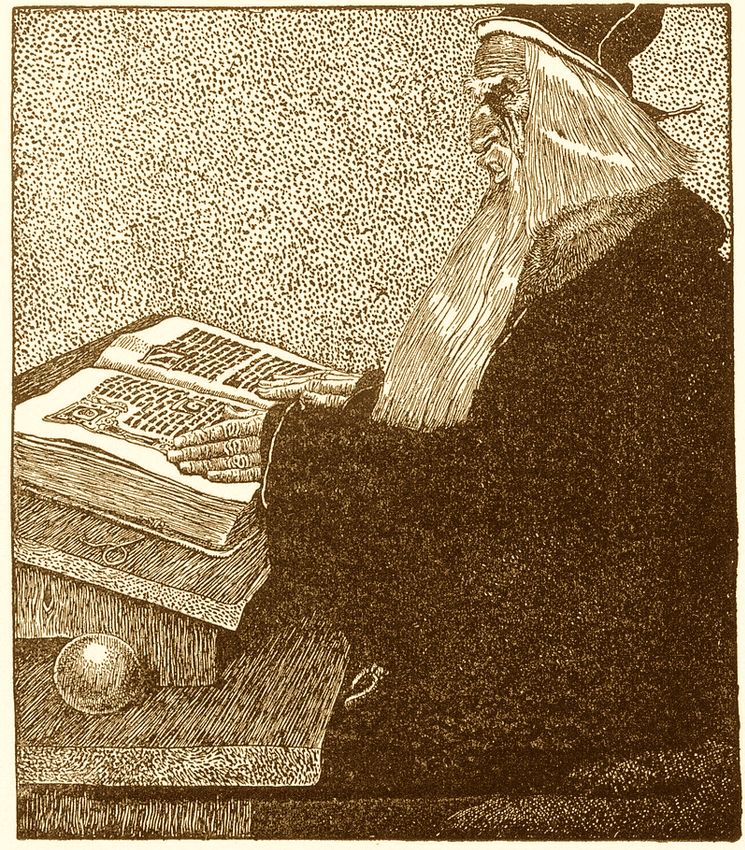

The word alchemy conjures up images of wizened and bearded sages poring over a massive leather-bound volume, crowded by various beakers, flasks, crucibles, a human skull or two, and, of course, the ubiquitous retort over a flame and glowing a preternatural green. We always know what they’re up to; the silly coots are attempting to turn lead into gold. Good thing we’re not that stupid anymore! (Apologies to the twits running the Federal Reserve Bank). What one may discover, though, is that alchemy, in actual fact, was just as crucial to the evolution of civilisation as art, religion, and all the rest of it.

The usual definition of alchemy: the medieval forerunner of chemistry, concerned with the transmutation of matter, in particular with attempts to convert base metals into gold or find a universal elixir.

A better definition: the field of the processes of transformation, creation, and combination both of matter and spirit and how they interact with the Absolute.

Dictionary.com actually does a good job with the origin: First recorded in 1375–1425; earlier alchimie, from Old French alquemie, from Medieval Latin alchymia, from Arabic al “the” + kīmiyā’, from Greek khymeía, also khēmeía “art of alloying metals; alchemy”; replacing Middle English alconomye, equivalent to alk(imie) + (astr)onomye “astronomy”.

An older, mostly speculative, etymology derives chēmeía (khēmeia) from an unrecorded Greek verb chēmeúein “to work in an Egyptian way,” from the Egyptian name for Egypt, Chēmía (Coptic Chēme, Chēmi or Kēme, (hieroglyphic: 𓆎𓅓𓏏𓊖) “Black Land,” so called in reference to the dark earth of the Nile Valley which was auriferous (gold-bearing).

The roots of alchemy are numerous and span six millennia at least. One source is as a branch of natural philosophy and primitive scientific traditions that can be traced to ancient China, India, and Mesopotamia. Later, Greco-Roman Egypt produced whole bodies of alchemic works, which were subsequently translated into Arabic and Latin in the first few centuries A.D. In a word, this stuff is pretty old.

Islamic and European alchemists developed prototypical laboratory techniques, drew up theories and conducted experiments, and created a lexicon, some of which is still in use. They expanded on the ideas of the earliest Greek philosophers, who were investigating the fundamental elements of matter and life, such as water, air, earth, and fire. Early European alchemists tended to guard their work jealously, often making use of cryptic symbolism, which created some confusion as to what was being worked on and was certainly a factor in adding to the alchemic mystique. Magic symbols! Actually, these symbols were mostly used to obfuscate jealously guarded data. The Moslems, on the other hand, often shared their discoveries and methods openly with any curious investigators, which was very lucky for humanity.

An early source of alchemy as we know it today was Zosimos of Panopolis (300 A.D.). He wrote some of the oldest known works on what eventually came to be called “alchemy,” which he termed “Cheirokmeta,” or “things made by hand.” There have been many, many such geniuses over the centuries.

Another root was Hermeticism.

The Hermetic tradition

Hermetic: of, relating to, or characteristic of occult (hidden) science, especially alchemy. From Medieval Latin hermēticus of, pertaining to Hermes Trismegistus, equivalent to Latin Hermē(s) Hermes.

Hermes is, of course, the son of Zeus and Maia. He is the messenger of the gods, the god of merchants, and of thieves, and of oratory. He is also a “soul guide,” a psychopomp, or conductor of souls into the afterlife. He is portrayed as a herald equipped for travel, with a broad-brimmed hat, winged shoes, and a winged rod.

Hermes Trismegistus, Heremes “megistou kai megistou theou megalou Hermou,” or “Thrice Greatest,” however, is a syncretic (syncretism is the combining of different beliefs and various schools of thought) combination of the Greek god Hermes and the much older Egyptian god, Thoth. Thoth, the moon god, he of the head of an Ibis, god of wisdom, justice, and writing, patron of the sciences, and messenger of the sun god Ra. (Thoth was also a judge of the dead, along with the jackal-headed Anubis who weighed the heart of the dearly departed against a feather—uh-oh.)

The wisdom of Hermes Trismegistus is recorded in a number of texts, collectively called the Hermetica. The Hermetica, in the form we know them, are from the Ptolemaic (Hellenic) era4 of Egypt (305—30 B.C.) as well as later. It has no one specific author as the materials are records of oral traditions going back thousands of years. Hermeticism was also influenced by Greek philosophers, such as Pythagoras (570—495 B.C.), who were working on what systems (mathematical, etc.) most represented reality and how to live accordingly (ethics).

The earliest recorded Hermetica were written in Greek before being translated into Arabic and Latin. Others were written only in Arabic, but eventually these were also translated and copied many times during the Middle Ages.

The Hermetica contains knowledge of both the material and spiritual worlds and the interrelationship between the material and the divine. Renaissance scholars originally thought that the wisdom might have originated with Moses (1391—1271 B.C.) or even Abraham (2200—1900 B.C.), but it is probable that it is much older. There are also other manuscripts, sometimes referred to as the technical Hermetica. All in all there are more than three hundred and sixty texts.

The subjects of medicine, pharmacology, alchemy, magic, and astrology are all covered in the Technical Hermetica. The Spiritual Hermetica is about the spiritual, divine, and philosophical aspects of being.

It is very interesting to note that, in the earlier years of the Renaissance, Cosimo de’ Medici (1389–1464), in around 1462, told his scholars to leave off translating Plato to translate and transcribe a new batch of folios, which would become known as the Corpus Hermeticum. These manuscripts, produced by his court translator, Marsilio Ficino (1433–1489), had an enormous influence over the Renaissance period. The symbols of Hermeticism eventually appeared everywhere: the caduceus (the great wand with two snakes wrapped, double helix-like, around it), along with symbols of Egyptian antiquity: pyramids, obelisks, winged sun disks, all-seeing eyes, etc., came to be mainstays of the Western esoteric landscape (hellooo Freemasons!).

One of the manuscripts of the technical body of Hermetic knowledge is the Emerald Tablet.

The Emerald Tablet

This was a centrepiece of medieval and Renaissance alchemy. There were quite a few commentaries and translations published on it by such luminaries as Albertus Magnus (1200—1280), Roger Bacon (1219—1292), Johannes Trithemius (1462—1516), and Sir Isaac Newton (1642—1727), who, interestingly, translated it into English. It describes the basic ideas of alchemy and speaks of the mysterious philosopher’s stone.

The philosopher’s stone is an alchemical substance capable of turning base metals, such as mercury, into gold or silver. Or, perhaps, it is the elixir of life, used for rejuvenation and for achieving immortality. Possibly, it is both.

It is also something else, something perhaps far more valuable: it symbolises perfection, enlightenment, and heavenly bliss.

Through the ages, these were the most well-known goals in alchemy: the transmutation of metals and immortality. The project to discover and properly use the philosopher’s stone is known as the Magnum Opus, or Great Work.

Hm.

Having thought about this a little, especially this business of transmutation of metals, any modern metallurgist is going to agree that there might be something to it because they know how to produce alloys and such like. Not quite transmutation, but the making of many different kinds of metals and chemicals by mixing them with other things, using heat and cold, and so on. As to making gold out of lead, well, there is not a whole lot of concrete evidence there (as in none), and that is what it takes, apparently, to write alchemy straight out of the science history books. Strike!

There are records of it being accomplished, though, which is interesting. I surely don’t know if the observers were mistaken or fooled (studying the observations of cause and effect, especially as recorded in the Middle Ages, is often very poetical; “moon rain” causes morning dew, etc.), but I wonder about this sometimes. What if it was accomplished but that the process was far more expensive than the result? Like ethanol, an alternative to petrol, its production currently consumes far more energy than the final product, rendering it impractical as well as uneconomical. Then there are the linear accelerators like the ones at Darmstadt, Heidelberg, and Berkeley, which can, at an even vaster expense, fuse tin (atomic number 50) and copper (atomic number 29), making gold (atomic number 79); 29 + 50 = hey presto! Not that any alchemists of old had these machines, of course, but it does demonstrate something is possible. (One wonders how many technologies have been lost compared to what we know now.)

Besides, if making gold were accomplished cheaply enough, it would have destroyed whole economies through inflation, such as happened when the Spanish Empire flooded their own economy with all the gold they looted from the New World, and what the U.S. government, and most other governments, are doing right now with printing (also a form of looting, folks).

Then there is another thing to think about. It’s not exactly on point, but it’s also interesting. Using an online permutation calculator, how many possible combinations are there of the 118 known elemental chemicals, not even factoring in proportions of mixture and other variables like temperature? I tried to calculate it. The answer went, 46845258497542… on and on straight off the page. If someone out there sees that I screwed up, please let me know, but I think the point is, if you could take just one chemical, copper, and mix it with just the right amount of something as commonplace and easily found as tin, you could get not only bronze, but a whole new era in history, which is exactly what happened 5,300 years ago. To all the chemists out there, I say, have we even gotten started?

So I think, like the alchemists of old, the chemists of today can be forgiven that they haven’t discovered everything, and we can be glad they are still hard at work.

Just as interesting, though, is the other transmutation, the one of mind and spirit.

As above…

All through the religio-philosophic Hermetica is information about the transformation of being, the realisation of the self from one state into another, higher state.

The second verse of the Emerald Tablet, from the G. R. S. Mead translation, reads: “… whatever is below, is like that which is above; and that which is above, is like that which is below: By this are acquired and perfected the Miracles of the One Thing.”

I guess this is to point out that there is no real division or separateness between oneself and the cosmos. We can, however, differentiate ourselves in various egregious ways and therefore experience the pain and suffering of having come “undone” from what is above. As well as from that which is below.

What some call the subconscious lies below the mid-point of Earth and body: “visita interiora terrae rectificando invenies occultum” (“visit the interior of the earth and you will find the secret”). Ignoring its shadows undoes us all but good; it’s how one becomes unconnected with the above in the first place, apparently. There’s true gold down there, but beware, there lie also dragons.

The Kybalion

Polarity is another example of hermetic transmutation: In the Kybalion, published in 1908 and authored by Three Initiates (a nom de plume), is the most well-known 20th century work dealing with the Hermetic teachings.5 It states, “Everything is dual; everything has poles; everything has its pair of opposites; like and unlike are the same; opposites are identical in nature, but different in degree; extremes meet; all truths are but half-truths; all paradoxes may be reconciled.”

This is a reference to the relationship between the mind and the material. On a wholly material level, though, it can readily be seen in physics with the periodic table. Osmium is more complex and more solid and utterly different than hydrogen but is basically the same stuff. The same goes for the electromagnetic spectrum. The same goes for nous, mind, which covers both. The table and the spectrum, I mean, and goes much higher. A lot higher.

Anyway, this business of poles is particularly useful. Perhaps you are depressed. Depression is the polar opposite of enthusiasm. Put your whole attention on enthusiasm, pretend that life is interesting and engaging, and you can literally lift yourself up and out of a possibly debilitating degree of ennui. The same is true for boredom, fear, and anger, and so on. Possibly today, the place some of us find ourselves descending into is resentment. The opposite pole to resentment? Gratitude. (Incidentally, gratitude is a key component in… religion.)

Whatever pole you are on, find the other to affect change in reality, because reality is ultimately what one makes of it. This is actually what is meant in Scientology 1.0.0 by “being responsible for one’s own condition,” by the way.6 Besides, this utilises one of the most powerful forces in magic, the power of attention.

In the Kybalion it says, “’Attention’ is a word derived from the Latin root, meaning ‘to reach out; to stretch out,’ (Latin attendere, from ad– ‘to’ + tendere ‘stretch’). The act of attention is really a mental ‘reaching out; extension’ of mental energy, so that the underlying idea is readily understood when we examine the real meaning of ‘attention.’”

Mental energy. Strength and vitality. What one puts their attention on gets strengthened and vitalised. Animated. Take care with your focus! Ignore what doesn’t serve (if possible). Both the rose and the weed thrive when watered. The correct use of attention could change our whole culture.

As an aside, some forms of psychoanalysis continuously put the patient’s attention on where they have been at the effect of life, a victim, and this animates, therefore perpetuates, victimhood. By all means, talk the upset over but, as soon as possible, get the patient’s attention over and onto where they are at cause rather than effect, without making them out to be wrong (feel bad) and they may experience some relief at last.

This discovery of the axiomatic power of attention is very, very old and is a mainstay of Scientology 1.0.0. If one has difficulty doing the simple exercise of locating an opposite pole and shifting it up, or directing attention easily in any way, then it’s a pretty good indicator that an effective therapy may be needed.

Regarding the importance of recognising paradoxes: paradoxes are often seen as contradictions in the dualistic West, which is a shame because it makes it harder to learn wisdom. Contradictions are break-downs in logic, but paradoxes are different.

Some concrete examples are pertinent to our own times: Freedom can only be obtained through bonds (i.e., proper obedience to Natural Law rather than “do as thou wilt” or “each for themselves”). Liberty is attained by accepting constraints (i.e., self-imposed responsibility rather than licentiousness), and so on.

Those are sort of obvious, but other paradoxes, such as free will versus determinism, or the Big Bang versus Creationism, being weirder yet still apparently “demanding” to be either one way or the other, “may be reconciled.” In other words, to be able to think with paradoxes is to move with one foot on firm ground while the other is in the infinite (as in the Shaivite tradition, where Shiva is the Supreme Lord who creates, protects, and transforms the universe); to think “outside the box,” as they say.

This is the playground of imagination, what alchemists call imaginatio vera et non fantastica, where literally all our goodies come from. At lower levels of reality, and the adept is a master of all levels high and low, there are hard “yeses” and hard “nos,” but at the highest levels it is never “this or that,” it is always both. It’s only at the more solid levels of consciousness (both feet solidly planted on terra firma) that they might look like contradictions. (Nothing wrong with having both feet planted firmly as long as one remembers that life is more like a dance than a brick wall.)

Besides, the Truth is always humorous and not at all serious. Maybe many of the truths leading up to the Truth are horrible, serious, and hard to contemplate, such as those dragons previously alluded to, but not the actual Truth. The East is quite right to portray wise men laughing.

Three Initiates also warn of the dangers of advanced esoteric information. He puts it this way: “‘Strong meat for men,’ while [it is for] others [to] furnish the ‘milk for babes.’” This comes from Hebrews 5:14, “But strong meat belongeth to them that are of full age, even those who by reason of use have their senses exercised to discern both good and evil.” Also, the adept is responsible for reserving their “pearls of wisdom for the few elect, who recognise their value and who [will] wear them in their crowns.” This advice comes from Matthew 7:6, “Give not that which is holy unto the dogs, neither cast ye your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet, and turn again and rend you.” (A bit harsh, that bit about dogs and swine, but maybe Matt was having a bad day – or was still upset about what happened to his teacher.)

Why not, though? Why not risk casting pearls out to the world, letting them land wherever they may? Possibly it’s because when one imparts golden sounds to leaden ears, the would-be legatee often goes forth spouting the same noises but now without the music, rendering them as mere “words, words, words.” Others, hearing this dissonant rubbish and seeing plainly the train wreck that is so often the lot of such a person, will now themselves become deaf when otherwise they might have listened. In that scenario, the pearls are trampled in the mud.

Another reason might be the inevitable disruption of the status quo that such teaching will cause; changing conditions in the world is always a perilous thing. In the best case just mentioned, nobody hears. In the worst case, for the master anyway, people may turn on him and attempt to rip him to pieces. As Jesus at Calvary uttered, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do.” (Of course, Jesus knew exactly what he was doing; he was no victim.)

But then, there it is: Jesus still went forth and spoke wisdom to the people before being crucified. My opinion? He had no choice; it was time. In the early years of Rome’s deleterious dictatorships, withholding his information was a greater danger than imparting it, and today we are the better for it.

The same went for the beginning of the 20th century, when the Kybalion was published. (Three Initiates didn’t get crucified but that’s what pseudonyms are for.) The Theosophists7 knew this years earlier. Despite the very real dangers of imparting higher truths to a world possibly not yet ready for them, there come times when there are perhaps no better options.

On the other hand, interestingly, there is another factor. In the Kybalion it says,“Where fall the footsteps of the Master, the ears of those ready for his Teaching open wide.” Well, good! Possibly, teaching wisdom is simply always the right thing to do, come what may, because there are always those ready to learn.

Today, there are other perils besides having wisdom disregarded or being rent to pieces, such as man’s not being wise enough to handle high technologies like the technocratic state, thermonuclear weapons, central banking, pharmaceuticals, and social media. Withholding wisdom, come what may, becomes entirely unwise then.

These few examples are just the ones that were on my mind while writing this article. There is, of course, much, much more to the book as well as the subject as a whole.

The bottom line is that without some attempt to teach, nothing will change. The mind is how one sees the world, and if you want a better world, you first have to instruct the mind. Change your mind, and you change the world. As above, so below.

Many years ago, I read about Isaac Newton, the famous mathematician and physicist, who was the author of Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy). I didn’t see anywhere that he was also an alchemist, which is strange because he spent more time on that than figuring out the laws of motion and universal gravitation.

Later reading disclosed that many scholars were indeed aware that he had “alchemic and occult interests,” which are disclosed to the reader in a sort of apologetic, embarrassed tone; they think Sir Newton spent too much valuable time on it. I guess they thought it might hurt his reputation for us “modern rationalists” if we knew this, maybe because alchemy is often confused with the occult (“the occult! oooh, shiver!“). I mean, “who knows what more he could have discovered if he wasn’t such a time waster?” To those snooty experts, I say, how do you know he didn’t discover what he did because he was an alchemist, eh? The facts are that alchemy and all these hermetic writings were well known to all medieval and Renaissance thinkers, as well as those of the early Enlightenment, and were what helped give birth to the Age of Reason.

At the beginning of the 18th century, though, it’s true a codified distinction was being drawn between alchemy and chemistry. One could say that alchemy was growing up, and that people who stuck to the old writings and methods were soon left behind by people who looked at natural phenomena more closely.

Take what happened in the case of Robert Fludd (1574—1637). He was a prominent English physician with both scientific and occult involvements. He is interesting because of the debates he had with modern philosophers and mathematicians such as Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), who in turn was a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution. Kepler’s planetary observations led him to discover the three laws governing orbital motion, which in turn led to Newton’s theory of universal gravitation (this at a time when little distinction was made between astrology and astronomy8). Fludd’s support for a “declining” intellectual philosophy caused him to vigorously debate Kepler, but it also made sure that he would be mostly forgotten today. It’s through debate that scientists work out what theories to work on, how to work on them and so on. In this way, at least, he was a key figure in the rise of the new scientific paradigm.

Rushing on up to the near-present, there is Carl Jung (1875–1961), who was also an alchemist. His 1944 book, Psychology and Alchemy, is a pretty thorough analysis of alchemical symbols, re-evaluating them in the light of modern psychoanalysis. He was one of the greats who made clear that a useful understanding of alchemy is as follows: “the transformation of the impure soul (lead) to a perfected soul (gold).”

Science was on the rise three hundred years ago, and writers such as Charles Mackay (1814–1889) made it a point to emphasise the 18th and 19th century philosophers’ need to distance themselves from “charlatanism” and tear alchemy down. Hence, its gradual disappearance.

But in the 19th century, though, with the occult revival and despite detractors like Mackay and others, alchemy regained ground on the basis of its spiritual components.

Right. Well, that’s just the tiniest peek at alchemy.

We are the inheritors of the Egypto-Hellenic world as well as its Islamic preservers. If you wish to understand the foundations of chemistry, psychology, philosophy, etc., you can locate some of their roots within the Hellenic mysteries, which themselves have antecedents in ancient Egypt.

When it comes to spiritual matters, studying these subjects may give one deep insights into information and rules that you might not have thought much about before. Or maybe not. But there is no doubt that they played and continue to play a significant role in civilisation.

New alchemists are doing the same thing, and the Magnum Opus continues apace, albeit under different appellations. In fact, The Great Work is what a Scientologist is doing, whether they know it or not, just with newer tools. Those who engage in the deep learning available despite the distractions of this hectic world learn this pretty quickly. Besides, there are no secrets or hidden mysteries of wisdom these days, except for those unfortunates who cannot hear, or just don’t look.

My main point, though, is that alchemy is another whole field of enquiry lost to sight for most people today. Attending to it will most likely provide the interested seeker with entirely new tools and perspectives. Discoveries that could quite possibly yield extraordinary results.

The old is also new.

Next: Occultism.

1 Positioning is a marketing term that means where a brand, or product,stands in the minds of the public and how it compares stands out from the brands, products of other groups or competitors. The same technique can be used to familiarise people with unfamiliar ideas by comparing them with other comparable, but well known, ideas.

2 Most treatments for mental illnesses were interventional until the end of the nineteenth century, when very primitive forms of “talking cures” were first tried. All Scientology processes are carried out through precision communication, talking, and other forms such as mimicry, and that’s new.

3 Unlike, say, university courses, Scientology schools allow the students to study at their own pace, just as with its therapies, which cannot and should not be rushed but allowed to take the time necessary to gain release from psychic pain and discomfort. Obviously, this could be a problem for an organisation that works this way if their students were allowed to dilly-dally with extra-curricular interests.

4 The Ptolemaic period was the last period of a truly magisterial, mysterious, and ancient Egypt. It ended with Cleopatra VII Philopator and its conquest by Rome.

5 The full title is The Kybalion: A Study of the Hermetic Philosophy of Ancient Egypt and Greece. Yogi Publication Society, Masonic Temple, Chicago, Illinois.

6 This is another of those pieces of data that can be easily “weaponised.” Like all such things, responsibility runs on a scale and is applicable according to where one is on the scale and what is happening. Responsibility isn’t a hammer.

7 Theosophy is the movement founded in 1875 as the Theosophical Society by Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891) and Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907).

8 Astrology is the study of heavenly bodies as they influence human affairs, and astronomy is the observation and measurement of celestial objects, space, and so on.

3 responses to “Alchemy”

I can’t help it but I have to comment before reading the whole thing.

Here it goes:

1. I enjoy every drop of word you throw upon us!!!

2. Us Boomers… 😂 I am one of them

3. I wish one day I could meet you and shake hands and have some discussion

4. Dad was a super guy, he got us all entangled 😂 (little joke)

5. I wish I were a painter too. I draw little caricatures so I love Art and I am fond of your’s. My son is in Art school here in Athens, Greece.

Wasn’t that enough of exposing myself? 😂

Arthur, I wanna thank you (at the age of 62) for bringing back a shiny day like your father did.

Ok, now I shut up! 😂

LikeLike

Thank you for writing these gems. Fantastic summary of the subject! On the topic of transmutation, if you have interest, I recommend researching the works of Roberto A. Monti. During the early throes of Covid-lockdown-mania my husband and I took a ‘super important, totally work-related’ business trip to meet some colleagues in Oregon. One of them introduced me to the works of Monti, and showed me his own transmutation successes.

I’ve since duplicated the experiment, with some minor improvements, using retorted mercury (so very low probability of in situ Au hangers-on). We are in the process of constructing an EPA-approved Hg retort and melting furnace to finalize the experiment and pour a gold pin from the conversion.

The subject opened my eyes and got me researching the periodic table as we understand it today. That is a rabbit hole of depths! Walter Russell’s spiral design is of particular interest in understanding the periodic table three-dimensionally. Viewpoint of dimension haha.

LikeLike

Thank you for this. Interesting stuff! I’d be glad to know how you get on. I will definitely look up Monti as well as Russell.

LikeLike